A Guide to Understanding the Online Piracy Bill

If a day without Wikipedia was a bother, think bigger. In this plugged-in world, we would barely be able to cope if the entire Internet went down in a city, state or country for a day or a week.

Sure, we’d survive. People have done it. Countries have, as Egypt did last year during the anti-government protests. And most of civilization went along until the 1990s without the Internet.

Sure, we’d survive. People have done it. Countries have, as Egypt did last year during the anti-government protests. And most of civilization went along until the 1990s without the Internet.

But now we’re so intertwined socially, financially and industrially that suddenly going back to the 1980s would hit the world as hard as a natural disaster, experts say.

No email, Twitter or Facebook. No buying online. No stock trades. No just-in-time industrial shipping. No real-time tracking of diseases.

No email, Twitter or Facebook. No buying online. No stock trades. No just-in-time industrial shipping. No real-time tracking of diseases.

Q: What is the purpose of the bill?

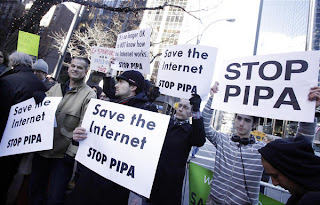

A: There are actually two bills, the Stop Online Piracy Act, known as SOPA, in the House and sister legislation called the Protect IP [Intellectual Property] Act, or PIPA, in the Senate. Both are designed to tackle the problem of foreign-based websites that sell pirated movies, music and other products.

Federal law enforcement has the authority to shut down U.S.-based websites that offer pirated content, but they can't directly do the same to foreign sites like Pirate Bay. The Motion Picture Association of America, the legislation's main backer, estimates 13% of American adults have watched illegal copies of movies or TV shows online, and it says the practice has cost media companies billions of dollars.

Q: How do the bills attempt to stop piracy?

A: The basic method is to stop U.S. companies from providing funding, advertising, links or other assistance to the foreign sites. The bills would give Justice Department prosecutors new powers to prevent pirate sites from getting U.S. visitors and funding.

Q: What are the new powers?

A: The Justice Department could seek a court order requiring U.S. Internet providers to block access to foreign pirate websites. Access could be blocked either by making it impossible for users to type a simple web address into an Internet browser to reach the site or by requiring search engines like Google to disable links to the sites.

The attorney general could also seek a court order requiring credit-card processors to stop processing payments to the sites and requiring advertising networks to stop placing ads on the sites or taking ads from the pirated websites for display elsewhere.

In addition, both bills would allow Hollywood studios and other content owners to take private legal action against websites that are alleged to be hosting pirated material.

The legislation would allow content owners to ask a court to require credit-card companies and advertising networks to stop payments to sites allegedly hosting pirated material.

Q: How does this harm free speech? A Wikipedia official said the legislation could allow for "censorship without due process."

A: Opponents of the legislation worry that the language in the House bill is so broad that it would allow content owners to target U.S. websites that aren't knowingly hosting pirated content. This has been a particular concern of bill opponents Facebook, Wikipedia and Twitter, all of which have sites that depend heavily on content uploaded by users.

In an extreme case, opponents say, media companies could get a court order blocking payments to an innocent site, with the effect of shutting it down and stripping it of its rights to free speech.

Also, they say the legislation would encourage authoritarian countries that have already been trying to block content on the Internet they don't like.

Q: What about the charge that the legislation could undermine cybersecurity efforts?

A: One of the biggest issues for Google, eBay and other Internet companies is a provision that in some instances would require "DNS blocking." The domain-name system, or DNS, is an integral part of the Internet, ensuring traffic goes where it's supposed to when users type in a Web address like www.wsj.com or www.whitehouse.gov. Those addresses are converted into the series of numbers that make up a site's Internet protocol address.

The original legislation would have required Internet providers to redirect traffic away from pirate websites by blocking the conversion system.

The problem, according to cybersecurity experts, is that such redirection is also sometimes used by hackers to deceive Internet users and commit cybercrimes.

On Saturday, the White House issued a warning that it couldn't support the legislation if it included DNS blocking because of the possible impact on cybersecurity efforts.

This issue may be resolved. Last week, House Judiciary Committee Chairman Lamar Smith (R., Texas) said he would eliminate the DNS blocking provision from the House's SOPA legislation. In addition, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy (D., Vt.) said he would propose changing the Senate legislation to require more study of the cybersecurity concerns before implementing DNS blocking.

Q: What's the difference between SOPA and PIPA?

A: The bills are very similar. One major difference is that the House bill includes a provision making it illegal to stream unauthorized copyrighted content.

The provision has been called the "Free Bieber" provision by the legislation's opponents in honor of teen singer Justin Bieber, who became famous after posting videos of himself performing other singers' songs on YouTube.

Q: What would have to happen for the bills to become law?

A: The House's SOPA legislation is awaiting consideration by the House Judiciary Committee, which tried unsuccessfully to complete its review of the bill in December. That effort was derailed after a bipartisan group of House members, including Rep. Darrell Issa (R., Calif.), filed dozens of amendments and used stalling tactics to prevent the bill from being considered before Congress left for the holidays. The bill's main sponsor, Rep. Smith, said Tuesday he plans to reschedule the hearing in February.

The Senate Judiciary Committee unanimously passed the PIPA legislation in May, but it has been awaiting floor action ever since. Forty senators are co-sponsoring the bill. However one opponent, Sen. Ron Wyden (D., Ore.), has vowed to filibuster the bill if Senate leaders try to move forward. On Jan. 13, six Republican senators sent Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid a letter asking him to delay floor action until concerns are resolved. However, a procedural vote is still scheduled in the Senate for Jan. 24.

In short, the legislation has several hurdles in both houses of Congress. If both houses pass the bill, President Barack Obama would have to make the choice: To sign or to veto. The White House on Tuesday reiterated that it has concerns about the legislation but agrees with proponents that more needs to be done to stop piracy.

No comments:

Post a Comment